I loved going to Cedar Grove. There was a huge field behind the two-floor school that housed 2 baseball diamonds and behind the field was a ravine where a small creek ran and sometimes after school we’d going hunting for frogs and tadpoles. The school had portables that some kids had to make their permanent classrooms. Those were the heady days of childhood were nothing was ever wrong in the world, and every day you’d wake up with a sense, of newness and adventure. Days where life was full of wonder and excitement, whether it was exploring the creek in the ravine, riding your bike to a friend’s home to watch Get Smart, or just collecting more and more bubble gum cards.

There were all kinds of games we played with the cards. There was a game called Shootsies where you’d face off against an opponent, and flick your card at wall, with the card that landed closest to the wall being the winner. The loser had to give up his card, so if you had a really precious card, you’d be an idiot to play it unless you thought you were going to win for sure. I played a lot of Shootsies, because the stakes were small and I wanted to keep my cards.

There was game called Kissies, where you’d keep shooting your cards against a wall, and when you landed on your opponent’s card, you won, and would take all the cards that had been played. Sometimes, this was one card if you landed on it right away and sometimes you could win several of your challenger’s cards. You really only played Kissies if you didn’t care if you lost some cards, or you were pretty confident about your flicking abilities. Kissies rarely resulted in you being skunked, where you lost all the cards you had in your hand.

The card games got even more competitive, with Knockdowns, being the next game in the skill hierarchy. In this event, you’d put a card leaning up against the wall, and the goal was to shoot one of your cards at the leaner card and knock it flat. Sometimes this happened right away, but more often than not, it would take several cards on both sides to knock down the standing card. This could result in a big loss or big payday! This was my favorite game. I just seemed to be pretty good at it for some reason.

The final game was Leaners. This was the game with the biggest potential stakes. The quest here was to shoot your card at the wall and get it to land so it was standing up on the wall. This was really tough to do, especially if your cards were new or you kept them in mint condition. Everyone had their special leaners card, that was worn in and usually a little bent.

Sometimes, you’d take a card and try to bend it or crumple it a little bit, to increase the chance that the card would float to the wall and settle in to a standing position. However, it didn’t always work that way. Sometimes these worked over cards were too soft and worn in and would just flop to the ground and not even make it to the wall. Leaners was a tough game and you could easily get skunked. It took a lot of guts to engage in leaner’s showdown.

There were other factors to consider when engaging in a battle of cards, depending on the game being played. Distance to the wall, ground surface, wind and rain were all variables that one had to consider in any given match. As a kid, you didn’t consciously think about these things. You just kind of knew. Probably, the most important factor that could influence a match’s outcome was wind. Maybe not so much in Shootsies or Kissies, but wind could wreak havoc with Knockdowns or Leaners.

We were fortunate at Cedar Grove though. We had “The Box.”

The Box was a large rectangular area at the back of the school that was sheltered on 3 sides from the elements. It was really the back door out of the gym, but was deep and long enough, that it was sheltered from the wind and rain. It became the main ring for any card duels, but there was a hierarchy to its use. You see, in the school yard, dominance was determined by aggression and grade, and in that order. Failing to comply, usually resulted with a punch in the face or worse. I was in Grade 3, and was low on the pecking order. To make matters worse, I was a pretty gentle kid, who shied away from confrontation. So, my friends and I rarely got to play in the box unless it was after school. At recess or lunch, there no chance in hell, that we’d get near it. The older grade guys would monopolize it as they engaged each other for bubble gum card dominance. The box always had crowds of kids looking on to see who was battling. The guys in my grade, usually played against the back wall of the school or against the portables, but that really sucked, especially in the late fall when it started to get cold. The box provided some shelter from the wind, so it wasn’t nearly as cold. Some of us even tried playing with gloves or mittens, but that was pathetic. You couldn’t control anything you shot. As fate would have it, I did get a turn at the box one late October day, during an afternoon recess.

I happened to get a Gordie Howe all-star card in my most recent purchase of cards. I was ecstatic. The Gordie Howe all-star card was a limited edition. There were hardly any of them around. If you looked at guy’s checklist, it was almost always the only card remaining to complete a full list. I was never sure why it was so important to have your checklist completed. It was just one of those things that kids kind of knew without having anyone tell them. When you played card games, the checklist card had almost no value, but everyone wanted their checklist completed! Well, I couldn’t help but show off the card when I got to school. My friends couldn’t believe my luck, and soon word got around the school that a Grade 3 kid had picked up the Gordie Howe all-star card. I become a celebrity of sorts, and reveled in my new-found popularity, until Tanzer approached me at lunch break.

Tanzer was a grade 6 kid. I had never met him, but he and his gang monopolized the box almost all the time. He was part of the cool, older guys, that wouldn’t ever even look at a grade 3 kid. Long, straight black hair, surrounding a thin, angular face, Tanzer was King of the Card games. He always had cards in his hands, and I wondered if he even brought them into class. He hung out with some other guys, that I’d heard had been in some trouble with the principal, Mr. Brown. I think they’d all been caught smoking near the ravine, but they never bothered with the little kids, unless it was to clear us out of the box.

So when Tanzer approached me at lunch, I was a little surprised and a lot scared. He didn’t say hello, he just said, “You the kid that got the Gordie Howe card?”

His gang stood behind him looking kind of bored, like what the hell was he doing talking to me. I noticed that his eyes shifted back and forth and his hair looked a little greasy from this close.

“Ya”, I answered hesitantly, worried that if I said too much, he’d smack me. I’d seen his gang in fights before.

“Lemme see it”, he gestured with his pointy chin towards my cards.

I pulled out the card and he looked at with ferocity of a lion about to pounce on a lamb.

“I’ll play you for it at this afternoon’s recess.”

I pulled the cards away. I didn’t want to play him. I’d seen him play in the box before, catching a peek, between torsos and legs. He was really good. I’d seen him skunk guys almost at will, at any of the games.

“I’m not sure”, I stammered. His gang behind him seemed to grow taller.

He looked at me for a moment. His eyes narrowed and his face got a little red.

“One way or another, I’m getting that card kid.”

I knew he meant it. I simply nodded my head slowly. He began to walk away, and turned to me again. “Leaners in the box at afternoon recess,”, then Tanzer and his gang disappeared behind the portables.

Leaners! I was beside myself. I wouldn’t just lose the Gordie Howe card. I’d lose all my cards.

My friend Larry had watched the exchange from a distance. I explained what had transpired.

“What are you gonna do?”

“I don’t know. I gotta play him or he’ll kill me.”

“Shit, the Gordie Howe all-star card”, he whispered in disbelief. “Maybe tell Principal Brown."

“If I do, I’m as good as dead”, I said. The lunch bell went off and I reluctantly trudged my way back to class. The afternoon dragged by and I couldn’t focus on long division or capital cities of the provinces. I thought about telling my teacher that I was getting sick and had to go home. Mrs. Bates was a kind, matriarchal woman and would probably let me go as I only lived around the corner from the school. But I figured there was no good away out of this and I’d have to play Tanzer sooner or later now that he knew I had the card.

The 2:30 afternoon recess bell reverberated through the halls and reluctantly I made my way to the box. Larry and a few friends followed me, as the crowd of onlookers parted way for me. Tanzer stood in the box, and his buddies gathered around him.

“Ready kid”, he said and smirked at one particular guy with long, greasy brown hair, who I always saw smoking near the far baseball diamond. That guy scared me. There was a funny look in his eyes, like he wasn’t really all there, and he was always getting into fights with Grade 7 and 8 kids.

“I guess”, I stammered and moved into the box with Tanzer as his cronies took their places on the periphery.

“Leaners kid”, he chortled, “and you shoot first."

I realized that he didn’t even know my name. I was some punk ass grade 3 kid who he would skunk and get the Gordie Howe card he so much coveted.

I pulled my cards out of my jacket pocket, grabbed the first card, gave it a little bend so it would have a higher chance of leaning up on the wall. I wondered if I’d get lucky, and my first shot would finish the game. I was gonna save the Gordie Howe card. The card sailed up to the wall, and settled in a horizontal manner. If we had been playing shooties, that would have been a great shot.

Tanzer flipped an old beat up card at the wall, that also slipped into a flat position.

His buddy with the crazy eyes, looked at the card I had thrown. “Tell him to play the card you want. He’s holdin out!”, he growled.

Tanzer looked at me and pointed at my cards. “Play the Howe card.”

Reluctantly, I pulled out the card. I couldn’t bend the Howe card. That would-be sacrilege. Carefully, so as not to damage the card, I flicked it ever so gently towards the wall, and the Howe card settled in close to the other two.

Tanzer shot next and we went back and forth for a few rounds with no leaners. I realized after 5 rounds and no winner, that he wasn’t that good. For some reason I had thought he was the master of shooting card games. But he wasn’t. He just hung with a tough crowd and acted like he was. The game went on and cards began to pile up on top of each other. A couple of times, he got close to getting a leaner, and the crowd oohed and awed. Soon I was down to my last couple of cards and so was Tanzer. The big guy with the greasy, brown hair kept whispering in Tanzer’s ear, like he was giving him suggestions on how to shoot his cards. I looked out beyond the box into the school yard and it seemed like the entire student population was watching or trying to find out what was happening. I swear there were even some Kindergarten kids poking around.

Finally, we were down to our last card each. I had started with around 40 cards. Tanzer shot next. He bent his card and flicked it at the wall. The card floated up to the wall, flipped at the last second and landed horizontally on the wall, on top of the already played cards. The crowd began to disband as I felt tears begin to roll down my cheeks. I had almost been skunked. I had lost the Gordie Howe card.

“Wait”, Tanzer shouted and pointed to the last card I was holding on to.

“I’ll give you a last chance if you want.”

I wiped away my tears and looked at the card. It was a Ron Ellis card, some guy who played for the Toronto Maple Leafs and wasn’t worth much as it was a common card. What the hell, I thought to myself. Why not? Might as well be skunked.

I stepped back into the box, and took my shooting position. The crowd which had partially disbanded returned to their previous spots. I pinched the top left corner of the card, flexed my wrist, took aim at his card leaning on the wall and quickly extended my wrist firing my card.

The Ron Ellis card took off from my hand like it was shot from a cannon and careened into the mass of cards 3 to 4 inches in front of Tanzer’s leaner. What a crappy shot I thought to myself. It was short of the mark. It skidded along the floor of cards and struck the leaner at its base, knocking it down and flipped up on the wall.

For a moment there was only silence, and then the crowd roared in disbelief. Tanzer’s eyes went wide, and he kept looking from the cards and then to me. His buddy looked pissed, and brushing Tanzer aside, started to pick up the cards like Tanzer had won. I wasn’t sure what to do next. I was scared of Tanzer and more frightened of his friend.

“Hey asshole put those cards back. The kid won fair and square. Tanzer locked eyes with his friend, who hesitated, dropped the cards he had already picked up and stepped closer so they could have a further discussion.

“You won Tanz. You gave the kid an extra shot.”

“Doesn’t matter. I’m good for my word. Kid got lucky but I ain’t cheating him.”

I listened to the exchange immobilized by disbelief. Tanzer had a soul. He was more than a chain smoking punk that preyed on little guys.

“Then just take the Howe card”, said greasy hair and fished the card out of the pile.

“Nope Levi. Give the kid his cards and let’s get outta here.” Greasy hair had a name. He dropped the cards, glared at me for a second, brushed his hands through his oily scalp, and they wondered off into the school yard.

I moved to gather my winnings with Larry right behind me.

“Holy Shit!. You skunked Tanzer”, Larry said incredulously and looked at me like I something out of the Mod Squad.

“Sort of”, I said and began to gather up the cards as the bell shrilled through the school yard. Carefully, I sought out the the Gordie Howe and Ron Ellis cards. These two cards, I put in my back pocket and the remaining were placed in my jacket.

The afternoon slowly evaporated into the end of the school day, and I made my way home, on the lookout for Tanzer and Greasy Hair. I took the Ellis and Howe cards out of my back pocket and hid them in my drawer at home. A drawer where I only put the most special things like my diary and special report cards.

I didn’t see much of them for the next few days, and when I did, Tanzer kind of looked at me like I was just another kid. He never bothered me or tried to play me again. I kept playing cards and every now and then, I’d get a chance to play in the box, but only for small stakes and against kids my own age. Eventually we moved onto to other recess and lunchtime pursuits like handball and yoyo challenges and playing cards moved to the wayside. But I never forgot beating Tanzer in the box.

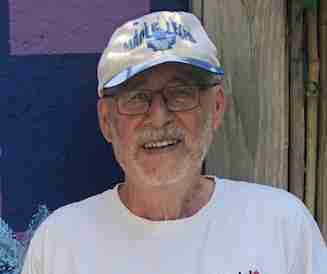

Andy at 78; Husband, Father, Grandfather, Survivor Speaker, Writer, Author, Motorcycle rider, and taxi industry veteran. He tells his kids that he has a Phd. in life skills but they don’t listen.

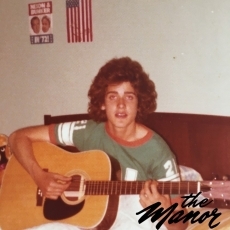

Andy at 78; Husband, Father, Grandfather, Survivor Speaker, Writer, Author, Motorcycle rider, and taxi industry veteran. He tells his kids that he has a Phd. in life skills but they don’t listen. In response to the OJA’s call for Bathurst Manor stories, Allan Rosenfeld contacted the OJA eager to share his memories of growing up in the Manor. He had a story to share—in fact, he had several. Rosenfeld’s short story The Box, is set at Cedar Grove Public School. The drama unfolds as a young Allan is challenged to a game of Leaners where he risks losing his entire bubble gum trading card collection, including his prized Gordie Howe all-star card.

In response to the OJA’s call for Bathurst Manor stories, Allan Rosenfeld contacted the OJA eager to share his memories of growing up in the Manor. He had a story to share—in fact, he had several. Rosenfeld’s short story The Box, is set at Cedar Grove Public School. The drama unfolds as a young Allan is challenged to a game of Leaners where he risks losing his entire bubble gum trading card collection, including his prized Gordie Howe all-star card.

Allan Rosenfeld grew up in Bathurst Manor. He is a physician, writer and author of several award winning medical short stories. He recently adapted his self-published book Holocaust Lumber, a story of growing up as a child of Holocaust survivors, into a play that finished third nationally in the 2019 Miles Nadal Jewish Playwright contest. His current project is entitled "Tales of Growing up in the “Manor.”

Allan Rosenfeld grew up in Bathurst Manor. He is a physician, writer and author of several award winning medical short stories. He recently adapted his self-published book Holocaust Lumber, a story of growing up as a child of Holocaust survivors, into a play that finished third nationally in the 2019 Miles Nadal Jewish Playwright contest. His current project is entitled "Tales of Growing up in the “Manor.”

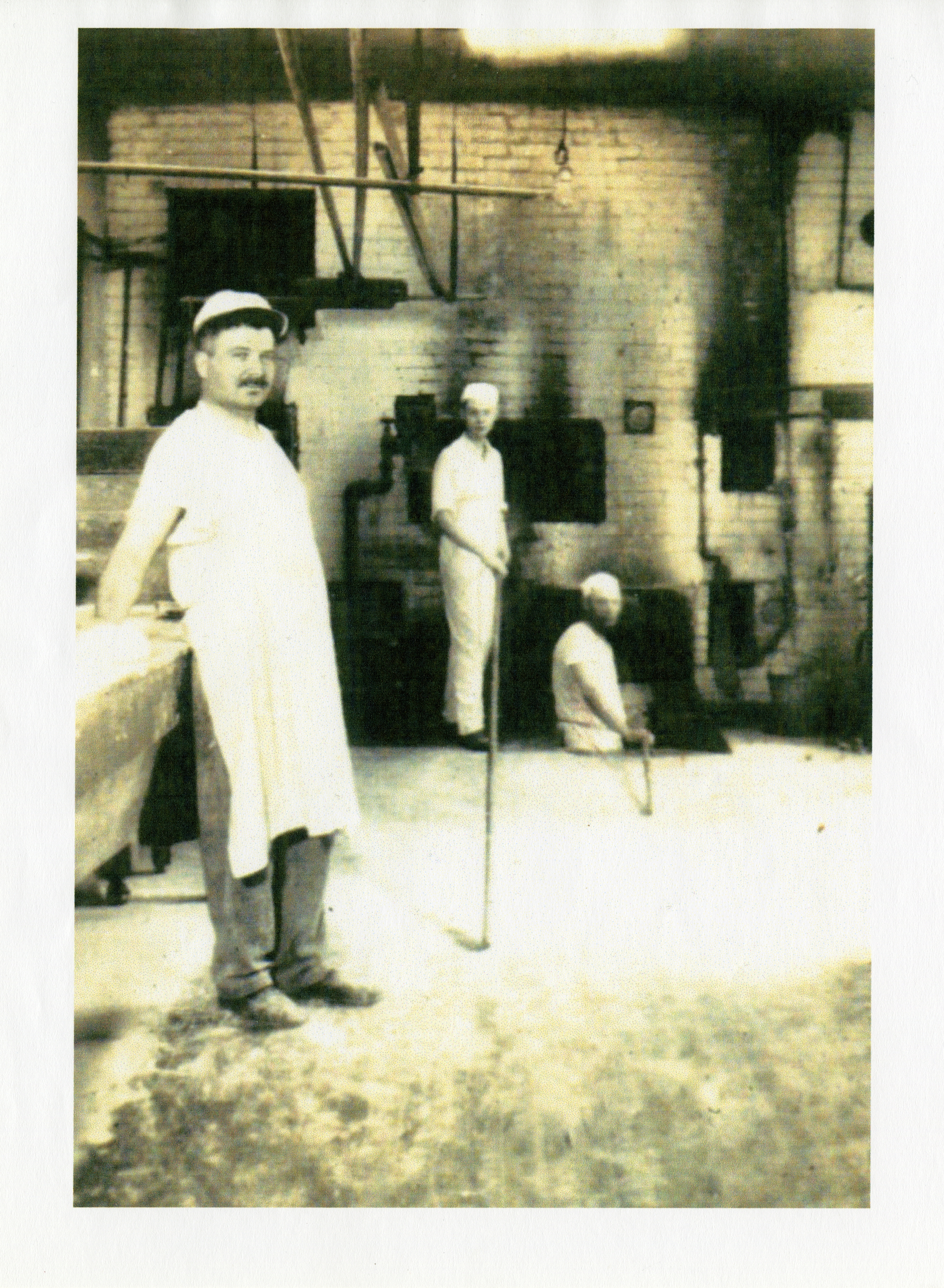

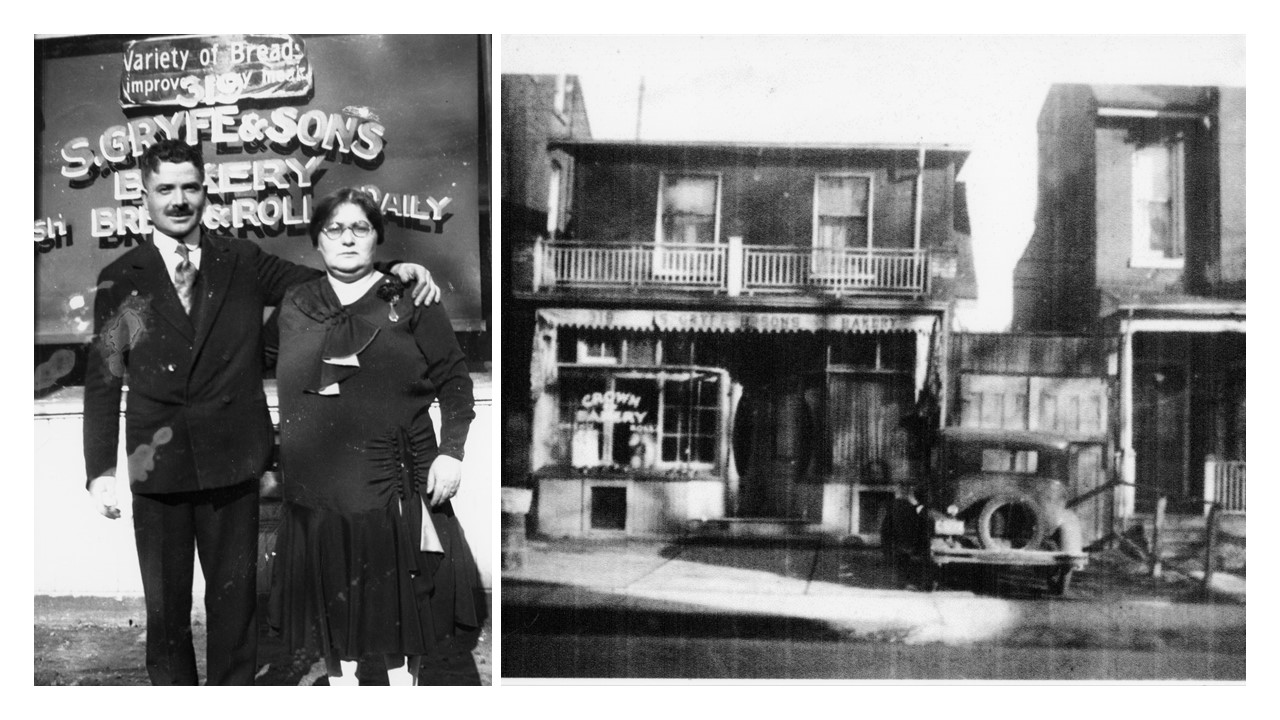

Cyril Gryfe is a retired physician, who specialized in geriatric medicine. Listening to his patients report their medical symptoms within the context of their long and often complicated life stories, perpetuated and reinforced his interest in history in general, which had been kindled during high school studies. Throughout his professional career this was focused on the history of medical practice, and in more recent years he has also devoted much time to the genealogy of his extended family.

Cyril Gryfe is a retired physician, who specialized in geriatric medicine. Listening to his patients report their medical symptoms within the context of their long and often complicated life stories, perpetuated and reinforced his interest in history in general, which had been kindled during high school studies. Throughout his professional career this was focused on the history of medical practice, and in more recent years he has also devoted much time to the genealogy of his extended family.