Processing the United Ostrowtzer Hilfs Committee Collection

I began my journey at the Ontario Jewish Archives as a volunteer following the completion of my Master's of Information at the University of Toronto's Faculty of Information with the hope of gaining hands-on experience working in an archive. I was eventually brought on as a contract archivist for a particular project: processing the United Ostrowtzer Hilfs Committee collection.

I began my journey at the Ontario Jewish Archives as a volunteer following the completion of my Master's of Information at the University of Toronto's Faculty of Information with the hope of gaining hands-on experience working in an archive. I was eventually brought on as a contract archivist for a particular project: processing the United Ostrowtzer Hilfs Committee collection.

Established in 1924 and named after the town of Ostrowiec, Poland the Ostrowtzer Hilfs Farein initially functioned as a branch of the Ostrovtzer Shul. Its mission was to offer support to Ostrovtzers who had relocated to Toronto, providing small loans, medical aid, and fostering a sense of community. In the aftermath of World War II, the society expanded its relief efforts to aid surviving Ostrovtzers worldwide, eventually evolving into the United Ostrowtzer Hilfs Committee.

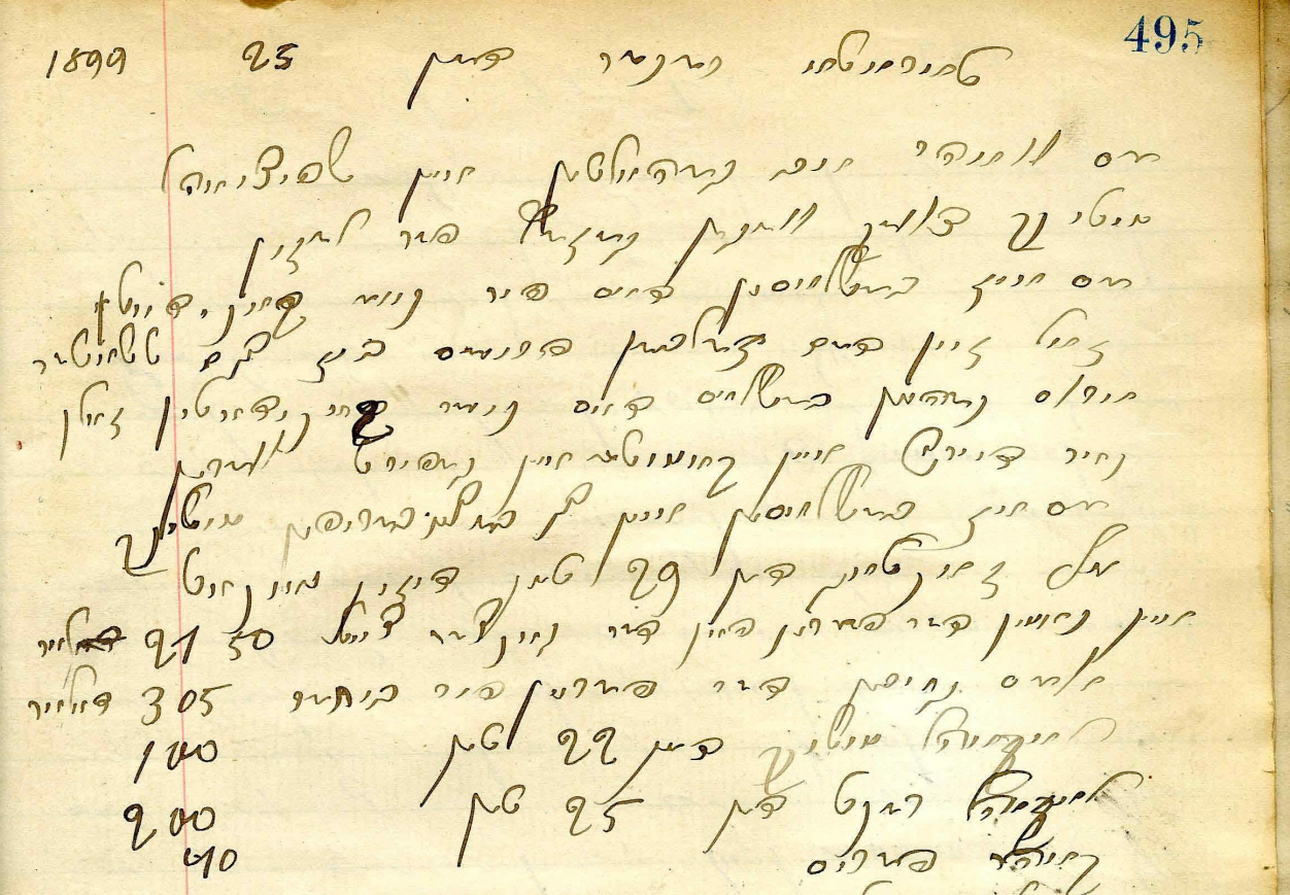

The collection mainly consists of over 300 letters from Ostrovtzer Holocaust survivors located throughout Europe and Palestine. These letters, written to Max Hartstone in his capacity as committee secretary, offer a unique glimpse into the immediate post-war experiences of Holocaust survivors, shedding light on their ongoing struggles even after liberation.

Over the past 5 months, I've had the privilege of working with this collection to preserve and make it accessible both in person and online. This entailed reading and re-reading the translations of every letter, researching the letter writers, scanning and uploading the documents to the archives' digital preservation system, inputting necessary metadata, and crafting detailed descriptions for each item. This work was made possible through a grant from the Rabbi Israel Miller Fund for Shoah Research, Education and Documentation at the Claims Conference.

Researching the authors often involved delving into concentration camp records, which was an emotionally taxing process. Many of these letters were difficult to read, as the authors recounted their experiences during the Holocaust and as refugees in displaced persons camps. Stories of losing spouses and children, or being the sole surviving members of their families, were distressingly common. The recurring phrase “lonely as a stone” exemplifies the profound sense of isolation that many of the writers felt. Many expressed the sentiment that corresponding with someone from their hometown provided them with much-needed solace. There was also hope expressed in these letters. Encountering stories of reunions with family members, marriages and recovery from illnesses was immensely gratifying.

I was deeply moved by the generosity of the Ostrovtzer community members who donated their time and resources to aid their fellow Ostrovtzers. The collective effort of Ostrovtzers worldwide underscore the camaraderie and community values within the Ostrovtzer community.

This experience has been both emotional and rewarding. I am very grateful to the Ontario Jewish Archives for giving me the opportunity to work with such a fascinating collection, and to develop my skills as an archivist. Though my time at the OJA has come to an end, I consider myself lucky to have worked with such an excellent team and look forward to working with them again in the future.

With Assistance from the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany

Supported by the Foundation Remembrance, Responsibility and Future and by the German Federal Ministry of Finance

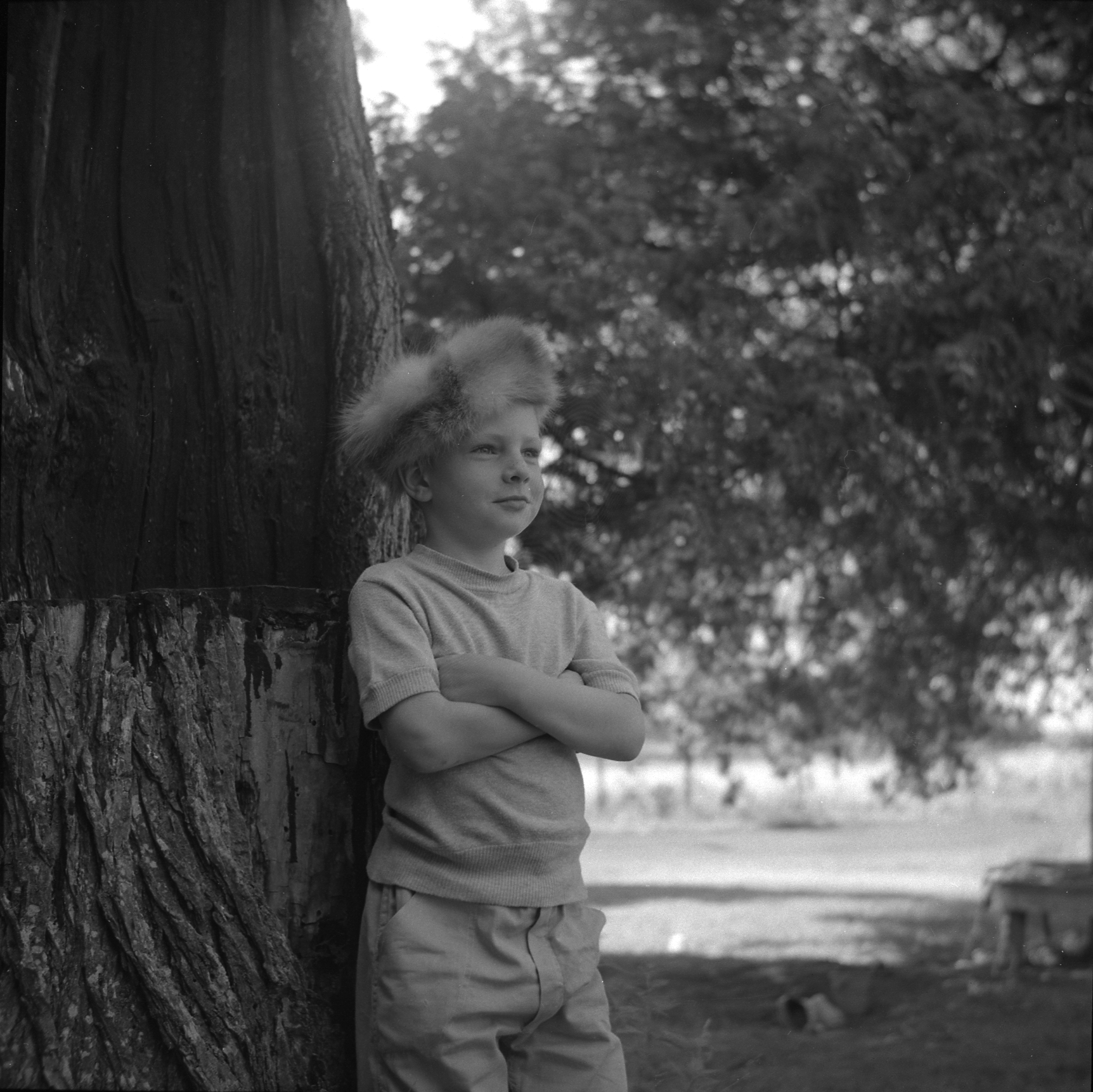

Not all of us are born into our families. In my case, and in the case of my adoptive dad, David Gruber, our families are mostly made up of people who chose one another; assemblages of dear friends, and often times their families. I grew up hearing fantastic tales of my dad’s Aunts Sylvia, Ruth, and Jewel Schwartz, and friends and extended families within the Toronto Jewish community. Stories of Jewel’s shop and the artists who moved through their lives, halcyon summers at the family cottage in Bobcaygeon where kids were free to fish and swim and canoe and roam under the watchful eyes of adults, the very best of life, days we would all live for.

Not all of us are born into our families. In my case, and in the case of my adoptive dad, David Gruber, our families are mostly made up of people who chose one another; assemblages of dear friends, and often times their families. I grew up hearing fantastic tales of my dad’s Aunts Sylvia, Ruth, and Jewel Schwartz, and friends and extended families within the Toronto Jewish community. Stories of Jewel’s shop and the artists who moved through their lives, halcyon summers at the family cottage in Bobcaygeon where kids were free to fish and swim and canoe and roam under the watchful eyes of adults, the very best of life, days we would all live for. When David – who I met when I was just 14 - died in March of 2022, the vacuum of loss he left behind led me on a search for ties to his past. Who he was and where he comes from has become who I am, and where I will go. The reach of my words ends when I think of the day I found these photos of my dad, digitized, and preserved by the Ontario Jewish Archives. His memories were suddenly made real. These documents, and photos of people’s lives, with their loves and their losses are alive in the stories we can tell and pass along. The world is a better place for having had them in it, and I believe it remains good with each remembrance of them.

When David – who I met when I was just 14 - died in March of 2022, the vacuum of loss he left behind led me on a search for ties to his past. Who he was and where he comes from has become who I am, and where I will go. The reach of my words ends when I think of the day I found these photos of my dad, digitized, and preserved by the Ontario Jewish Archives. His memories were suddenly made real. These documents, and photos of people’s lives, with their loves and their losses are alive in the stories we can tell and pass along. The world is a better place for having had them in it, and I believe it remains good with each remembrance of them. Andrea Taylor is completing a thesis for a Master of Arts in Disaster and Emergency Management while working with the Canadian Red Cross 2021 BC Floods Recovery Team. She and her rescue dog live next door to her son at their home in the west Kootenays.

Andrea Taylor is completing a thesis for a Master of Arts in Disaster and Emergency Management while working with the Canadian Red Cross 2021 BC Floods Recovery Team. She and her rescue dog live next door to her son at their home in the west Kootenays.

On a personal note, examining and working with the OJA’s documents has been both difficult and extremely rewarding, with content that ranges from the deeply upsetting to the humorous or joyous. The study of Yiddish is important to me for a number of reasons, not least of which is that it was the language of much of my family and my grandfather still speaks it. But beyond individual ties, translating Yiddish archival documents for today’s audience provides an important opportunity to preserve individual stories, moments of joy and sadness, that can resonate with all of us. To paraphrase my first Yiddish professor: you can say anything and everything in Yiddish. Preserving and sharing these words with a broader audience is a task I’m honoured to have played the smallest of parts in.

On a personal note, examining and working with the OJA’s documents has been both difficult and extremely rewarding, with content that ranges from the deeply upsetting to the humorous or joyous. The study of Yiddish is important to me for a number of reasons, not least of which is that it was the language of much of my family and my grandfather still speaks it. But beyond individual ties, translating Yiddish archival documents for today’s audience provides an important opportunity to preserve individual stories, moments of joy and sadness, that can resonate with all of us. To paraphrase my first Yiddish professor: you can say anything and everything in Yiddish. Preserving and sharing these words with a broader audience is a task I’m honoured to have played the smallest of parts in.