Scrap, Salvage and Sell: the Scrap Metal Trade in London, Ontario

If you have working-class Jewish ancestors who immigrated to Canada between the 1890s and 1930s, there is a good chance that one of your ancestors “started out” by selling second-hand goods or collecting junk (scrap).

In the early 1890s, my great-great grandfather Moses Leff and my great-grandfather William Leff settled in London, Ontario. They started by collecting scrap, rags, and second-hand goods. In 1898, William became a scrap dealer and founded his own business, “William Leff & Company”. My great-uncle Hyman Leff started a salvage business in the 1930s, and both businesses were in the family until the early 1970s. I was fortunate because I grew up hearing family stories about their lives in London, Ontario and about the scrap trade. However, I yearned to learn more.

This past year, I participated in the Morris Winchvesky Centre’s, Adult B’(nai) Mitzvah class, and was presented with a challenge of doing a project. I chose to do a project about my maternal family and their connection to the scrap business. The project can be found on the website: Scrap, Salvage, and Sell: the story of a Jewish family and their scrap businesses in London, Ontario.

During my research and interviews, I heard stories that I knew before: how my great-grandparents were the first marriage in the B’nai Israel Synagogue; how my great-grandfather William Leff co-founded the B’nai Moses synagogue; and that my great-grandmother Jennie co-founded the first Hadassah chapter in London.

I also uncovered new stories that I didn’t know before like how William and his employees were charged and fined for breaking the Sunday labour law in 1909. By diving into street directories and the census, I learned that in the 1920s, 90% of the scrap business owners and scrap collectors in London were Jewish. From a photo at the OJA, I learned that Max Lerner, a contemporary of my great-grandfather, started out as a scrap collector, and then became London’s first Jewish alderman. From my cousin ‘Aunt’ Ida, I learned how my great-uncle Hyman was “let go” from William Leff Company because he was blind. Not to be deterred, Hyman started his own scrap and building material company named the Hyman Leff Company. From newspaper articles and interviews, I learned about targeted arson attacks against the two businesses, and other Jewish owned scrap yards in 1948.

As part of the research project, I interviewed family members who have connections to both William and Hyman Leff’s businesses. These interviews shed light on their day-to-day operations, as well as what it was like to be a child of scrap and salvage brokers. These interviews form part the story on the website I created. When I finish editing and transcribing the interviews, I will be donating the interviews to the OJA, which will enrich their holdings on the Jewish-owned scrap industry.

The Value of Digitized Photos

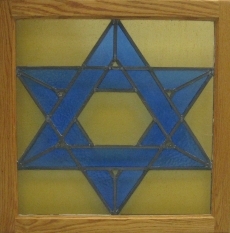

Many of the photographs in “Scrap, Salvage, and Sell” are from three archival donations to the Ontario Jewish Archives. The photos of the William Leff & Company business were donated by Zara Leff (daughter in-law of William Leff) in 1978. The photo of Max Lerner (former alderman in London, Ontario) was donated by Judge Mayer Lerner in 1993, and the stained-glass window from the B’nai Moses Synagogue was donated in 2000. Due to the past efforts of the OJA to digitize their photograph collections, I was able find these photos on the OJA website and use them for my own research.

As a researcher, I love the serendipity of finding hidden gems in digital libraries and archives. I am always grateful that someone had the foresight to donate photos, papers, and other documents to archives, so researchers can access them in the future.

In the past few decades many libraries, and archives, the OJA included, have been digitizing photographs with the goal of making their collections accessible to a wider audience. To date, the OJA has scanned upwards of 8,000 photos and documents from their collections which represents only a small fraction of their entire photographic holdings. Why have so few items been scanned? The answer is simple: it takes time, people, and funds to digitize collections. Sustained funding through donations is key to ensuring that even more documents and photos are processed, scanned, described, and made available for use.

Rosa Orlandini is a Data Services Librarian at York University Libraries.