Scandal Rocks the Toronto Jewish Community: Multiple Stories Unfold

By Nessiya Freedman

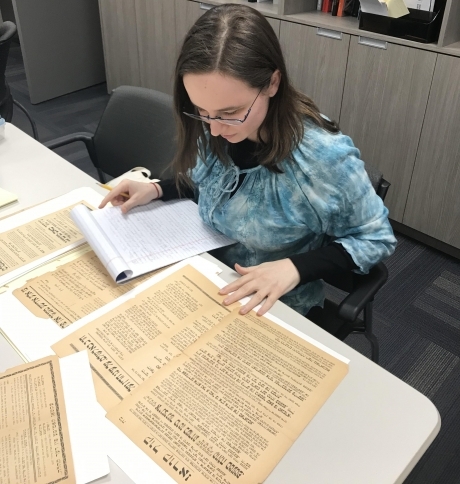

At first glance, it was an innocuous folder. It contained one set of yellowed flyers pertaining to kashrut, written in Yiddish, with no information to mark their origin save a single name: E. Miller or E. Mitler. The flyers resemble the style still popular today in Jerusalem’s Mea She’arim neighbourhood: a large, bold heading, followed by smaller text broken up by lines in medium to large sizes for emphasis, put up as public notices of various sorts to the neighbourhood at large.

This set of flyers, however, is from Toronto. It bears familiar street names: Spadina, Brunswick, Kensington, Queen, Dundas… The flyers also repeatedly mention a place known to those who grew up in Toronto in the last century: the Labour Lyceum at 346 Spadina Avenue, meeting place for unions and other members of the community until 1971. In the flyers, the Labor Lyceum serves as the location for mass meetings for causes as diverse as meat strikes and the formation of a new organization for the supervision of poultry kashrut, to protests against Hitler’s prosecution of the Communist Party of Germany in the wake of the Reichstag fire of 1933.

By the fifth document, a story familiar to the Toronto Jews of 1930 begins to coalesce. An outcry is arising from the community about butcher shops which have been operating outside of the supervision of the Toronto Rabbinical Board (or even outside of rabbinical supervision altogether), and therefore selling meat that is considered by the Kehillah treif (unkosher) and thus unfit to eat. Similar scandals rocked the Toronto Jewish community throughout the first four decades of the twentieth century: At first, there were butchers operating outside of rabbinic supervision, and possibly without even the proper certification for butchering kosher meat. The Kehillah, meaning “community”, of Toronto was an organization formed in 1923 specifically to oversee kashrut and thus eliminate the problem of treif meat being sold as kosher; however, the Kehillah faced so many problems that a rival organization, the Va’ad Ho’ir, was formed just under a decade later in an attempt to improve upon its efforts. (In Europe, kehillot were not limited to kashrut alone, but rather oversaw everything from education to the certification of rabbis, judges, and other public Jewish figures, and could even sometimes levy taxes. The Kehillah of Toronto was limited to ensuring the kashrut of meat from the start.)

In the flyers, Toronto Jews are reminded repeatedly that the only kosher meat is that which bears the Kehillah of Toronto kashrut stamp: no other stamps are valid. Lists are given of the butcher shops that are still under control of the Toronto Rabbinical Board (Va’ad HaRabbonim), with names and addresses. This listing of shops is repeated through so many kosher meat scandals that the Abram Brothers appear to have had enough time to expand from three shops to six. The scandal continues through the folder: “…[T]reif meat looks cheaper than kosher in all times, but even the poorest Jews would never, kholile, think to weaken our holy ways by paying a cent for it…” There is even a flyer begging Jewish women in particular not to buy meat that does not bear the community stamp (and to further tell their butchers, should they not be on the list of approved butchers, that they will buy no more meat from them).

It doesn’t end there: a flyer titled “Will the Call be Heard?” publicly chastises the rabbis and the butchers for their inaction in resolving the problem. The flyer is signed, “the Jews who still believe there can be kashrut instituted in Toronto.” Another flyer addresses the rabbis of Toronto, bemoaning their inaction and the false information floating around the community. (This flyer may well have been written after one in which the Rabbinical Board itself addresses the rumours running rampant in the community with a list of facts.) It ends by inviting delegates from all the organizations, unions, synagogues, and societies to “a conference of the entire city,” to be held on the 23rd of December, 2 p.m. sharp, at 350 Dundas Street West. It is signed, “a committee of city homeowners.” Yet another flyer calls upon the rabbis to make peace with the community over their alleged inaction during the kashrut scandal.

To date the flyers and the events they contain requires a certain amount of detective work. While some flyers mention weekday, day, and month, very few include the year, and many bear no date at all. It is also not so simple to identify them by event: Throughout the first four decades of the twentieth century, there were multiple butchery scandals with similar causes and even some of the same names. This makes it difficult to conclusively divide all the flyers even by decade. Certain clues do exist, such as the presence of the Va’ad Ho’ir (which was founded ca 1929 or 1930), and names like those of Rabbis Gordon and Weinreb (whose time in Toronto and involvement in various events are documented).

However, overall, similar issues resurfaced so many times that no flyer lacking such clues can immediately be identified with its decade of origin. Even the flyers reference the resurgence of similar issues, in such forms as accusations that the wholesalers profit every time there is an argument over butchery practices, as they become exempt from paying certain fees, or claims that with every strike the butchers’ union learns more about how to fight and the associated rabbis profit. A potential method for dating more of these flyers precisely would be to track down and examine the same documents and flyers that Stephen A. Speisman used to research his book The Jews of Toronto (which has been invaluable in identifying key players and events) and compare them with the contents of this folder.

There are several secondary threads within the folder. One is the price of meat, which was so high at fifteen cents per pound in 1933 or 1939 that it led to a strike. The strike raged, with meetings at the Labor Lyceum, and women joining the picketing even before the flyer that called them to come out in full force to picket for a success. A second outraged flyer called for the picketing of every butcher’s store after a group of women picketers, leaving an evening mass strike meeting to picket on College Street and others, was attacked by a group of “butcher-ruffians” (“butcher-khuliganes”) wielding knives. To the joy of the strike committee (and, presumably, the masses), the strike was won. The price of beef and calf meat was lowered to twelve cents per pound.

However, that was not to be the end: in the same flyer announcing their win, the strike committee takes up the cause of the community butchers. According to the committee, the popular cry that the butchers make thousands of dollars is “a hoax.” Instead, fifty percent is taken by the Butchers’-[Financial] Trust; thirty-five percent goes to the rabbis; and, of the remaining fifteen percent, a thousand dollars per year goes to a lawyer, forty-five dollars per week goes to a secretary, and thousands of dollars are used for advertising and miscellaneous costs. What, the committee asks, can possibly remain for the butchers themselves? They call the masses to a meeting, promising that they will be “astounded” when they hear all the facts about the Kosher-Meat Trust.

The argument that the butchers themselves saw very little of the money earned from their products bears similarities to the old struggle with the wholesalers, which had raged even in the previous decade. At various points in the 1920s and 1930s, public sentiment (at least as portrayed in the flyers from various communal organizations) was very much against wholesalers and private businesses. One such flyer, likely from the 1920s, contains the description of rich wholesalers “who stock their packets with poor [people’s] money.” The same flyer accuses wholesalers of profiting every time an argument about kashrut arises, presumably by managing to turn higher profits in the confusion.

Adding to the ill will against wholesalers, there had been since at the least the 1920s a problem of rabbis from outside (and even sometimes from within) the Va’ad HaRabbonim splitting off to certify the products of specific butchers and sometimes setting up private businesses, which earned more than the butchers who were part of the union and worked with the Va’ad HaRabbonim. At one point, even Rabbi Yehuda Leib Graubart, spiritual leader of the Polish Jewish community in Toronto since 1920, was accused of having taken six butchers and started up a business, thus effectively declaring war against the Butchers’ Union and the Kehillah. A presumably later flyer included in this folder contains the community response to his newly published Sefer Zikorn, or memoir. It begins: “Polish Jews, Hear a Horror!” In tones of absolute outrage, Graubart is taken to task for allegedly leveling accusations in this book which are more antisemitic than have been heard even from the greatest enemies of the Jews. The flyer ends with a call to the Polish Jews not to let this offence stand. The resolution is unfortunately neither included nor easy to track down; however, given that Graubart is remembered today as a great and learned rabbi and leader, it seems likely that, at the very least, the event did not ruin his reputation beyond repair.

There are other documents in the folder, covering such topics as protest meetings about Hitler’s actions in 1933 against the Communist Party of Germany; a commemoration evening marking the tenth anniversary of the Lithuanian-Latvian Jews’ annihilation (held at the Londoner Shul, which merged with Beth Emeth Bais Yehuda in 1975), the flyer for which entreats the community to “come all as one”; and a four-page memo from 1936 about yet more problems within the kosher meat industry. The most interesting is the longest and largest flyer in the folder: an open letter from the poultry butchers of Toronto to the community at large, ca the early 1920s. So big the original collector folded it in half to fit, the poultry butchers’ open letter to the community is well worth a thorough read. It teems with dramatic hyperbole and religious quotations and covers not only complaints but a sequence of events.

The letter first introduces the poultry butchers themselves, describing their poor working conditions. Unlike other workers with reasonable hours, it claims, the butchers must work throughout the day and night. And the job entails far more than meets the eye: They must bring the chickens to the right place, prepare them, deal with the expense of checking them—and all while being yelled at to “hurry up!” “Is this humane? Is this kosher?” Come to Kensington or Bathurst on a Sunday, the letter says; you will see butchers pulling wagons piled high with chicken coops!

In Europe and all of America, the letter continues, butchers are already “doing their holy work with a system”; only Toronto is still behind the times. The letter details how the butchers asked the Kehillah and the Toronto rabbis for help, but ultimately found them ineffective; they even obtained a ruling from the New York rabbinical association stating that poultry kashrut must be overseen by the Toronto rabbis and Kehillah, to no lasting success.

At this point, the topic changes. A man named Abraham Horwitz enters the scene. He has refused to sign the latest bargaining paper, when he had previously signed all of them and even taken responsibility for writing them. In the wake of this action his fellow butchers have decided to denounce him as an insolent man who always pushed boundaries. His actions, they claim, might be because he has four thousand dollars in the bank. They believe, however, that this is no excuse. Horwitz had even kept his shop open at a time when all others were closed awaiting arbitration. When he was called to a meeting where Rabbis Graubart, Weinreb, Gordon, and Levi were presiding, he allegedly responded by telling them they could all go to hell. Religious texts are then quoted by the butchers to the effect that a person with such behaviour is wicked, and that if said person is a butcher, he should be investigated by his community.

The letter ends in outcry: “Jews! Whoever is for God, follow me! Don’t be enablers of sinners! Jewish hearts! Should the Jewish feeling of mercy persist inside you, save forty families from being forever enslaved and ruined; help us! It will cost you no money to ensure we don’t have to work twenty-two hours out of every twenty-four—do not profit by the blood of your fellow! (Lev. 19:16). Give us a little clean air, free to breathe, so that our lives shouldn’t be consumptive and rheumatic, kholile.

“With bloody tears, we ask you to allow us to live! Our wives and children shouldn’t have to cry—have pity—we are living corpses! Hear our true and holy earnest voices! Help, Jews! Help us!”

It is signed, “the embittered, enslaved butchers of Toronto.”

Details regarding community history (particularly dates and some full names) were gleaned from Stephen A. Speisman’s The Jews of Toronto: A History to 1937, particularly chapter 17. All other details come from translation and analysis of the flyers themselves.

“Whoever is for God, follow me!” – the rallying cry of the Maccabees.

The translation of the Leviticus quote is from Sefaria.org.

Nessiya Freedman is a recent graduate from York University's BA Hon. Jewish Studies program. She is a language enthusiast and creative writer who has been volunteering at the OJA, and is now going to seek her fortune in Israel.

![Man examining poster, [Jerusalem], [1973?]. Ontario Jewish Archives, Blankenstein Family Heritage Centre, accession 2018-11-1.](https://ontariojewisharchives.org/cms_uploads/images/volunteers/Nessiya/i7-copy1.jpg)

![Manes Greenblatt, [ca 1929-1930]. Ontario Jewish Archives, Blankenstein Family Heritage Centre, item 56.](https://ontariojewisharchives.org/cms_uploads/images/volunteers/Nessiya/56-copy2.jpg)

![Standard Theatre movie poster collection, [between 1925 and 1935]. Ontario Jewish Archives, Blankenstein Family Heritage Centre, accession 2012-10-4.](https://ontariojewisharchives.org/cms_uploads/images/quotes/2012-10-4.jpg)

![Abe Goldberg collection, 1928-[ca. 1944]. Ontario Jewish Archives, Blankenstein Family Heritage Centre, accession 1982-7-6.](https://ontariojewisharchives.org/cms_uploads/images/quotes/1982-7-6_01.jpg)

![Standard Theatre movie poster collection, [between 1925 and 1935]. Ontario Jewish Archives, Blankenstein Family Heritage Centre, accession 2012-10-4.](https://ontariojewisharchives.org/cms_uploads/images/quotes/4274-copy1.jpg)

Tyler Wentzell is a historian in Toronto. He writes on military history and left-wing revolutionary groups, with a focus on the Great Depression and the Second World War. He is currently working on a book about William Krehm, the leader of the Toronto-based League for a Revolutionary Workers’ Party and a witness to the dramatic events in Barcelona in 1936-1937. Follow him @tylerwentzell

Tyler Wentzell is a historian in Toronto. He writes on military history and left-wing revolutionary groups, with a focus on the Great Depression and the Second World War. He is currently working on a book about William Krehm, the leader of the Toronto-based League for a Revolutionary Workers’ Party and a witness to the dramatic events in Barcelona in 1936-1937. Follow him @tylerwentzell