Benjamin Brown Preservation Campaign

Benjamin Brown (ca. 1888-1974) was one of Toronto’s first practicing Jewish architects and left an indelible mark on this city’s built heritage. Brown graduated from the University of Toronto architectural program in 1913 and that same year opened up a practice with fellow architect Robert McConnell, which lasted until the early 1920s. After the partnership ended, Brown continued with a highly successful independent practice until his retirement in 1955.

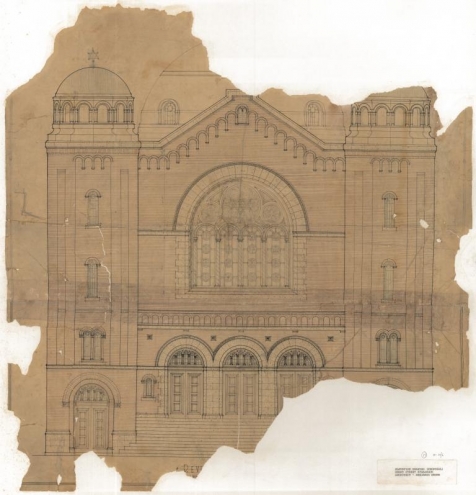

Brown stands amongst Toronto’s finest architects, having designed some of this city’s most magnificent structures, yet, he remains little known relative to other architects of the period. Brown primarily worked in the Art Nouveau and Art Deco styles, but also mastered many Georgian, Craftsman, Colonial Revival, Tudor and Romanesque elements. Buildings such as the Beth Jacob Synagogue on Henry Street, the Balfour and Tower buildings on lower Spadina Avenue and the former Primrose Club on Wilcox Street are still considered architectural gems today. Brown’s architectural style characterized the Spadina garment district for much of the 20th century.

The Ontario Jewish Archives, Blankenstein Family Heritage Centre is fortunate to have been the chosen repository for the extensive collection of Benjamin Brown’s architectural drawings, numbering approximately 1500 in total. His life’s work is captured in the original drawings, renderings, blueprints and hand-painted presentation pieces that range from the simple to the sublime. His projects included homes, businesses, industrial and commercial buildings, community institutions and synagogues—all represented in the OJA’s collection.

The OJA is embarking on a major conservation project to make critical repairs and to re-house the drawings to ensure their long-term preservation. In turn, this will drastically improve access to Brown’s most important works. The projects chosen for this phase of the conservation project include buildings that are significant to the history of the Jewish community and to the built history of Toronto, or are significant examples of the technical and artistic ability of Brown as an architect.

With your help we can preserve one of Toronto’s most important architectural collections!

To donate, contact Donna or call 416-635-5391 ext. 5170

To learn more about Benjamin Brown's prolific career, click here.

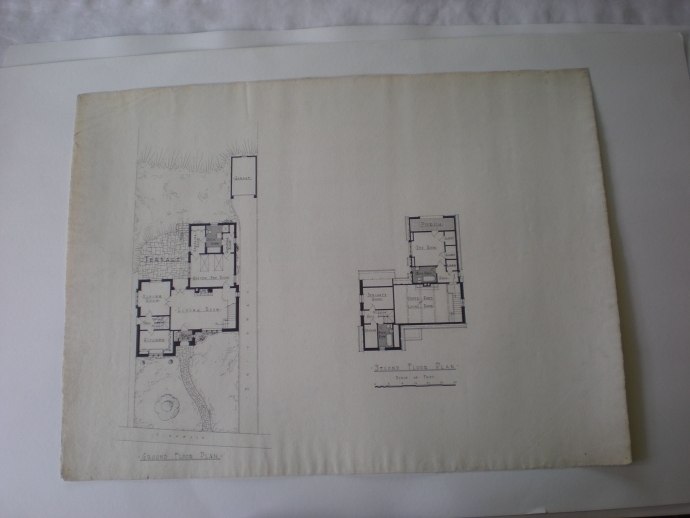

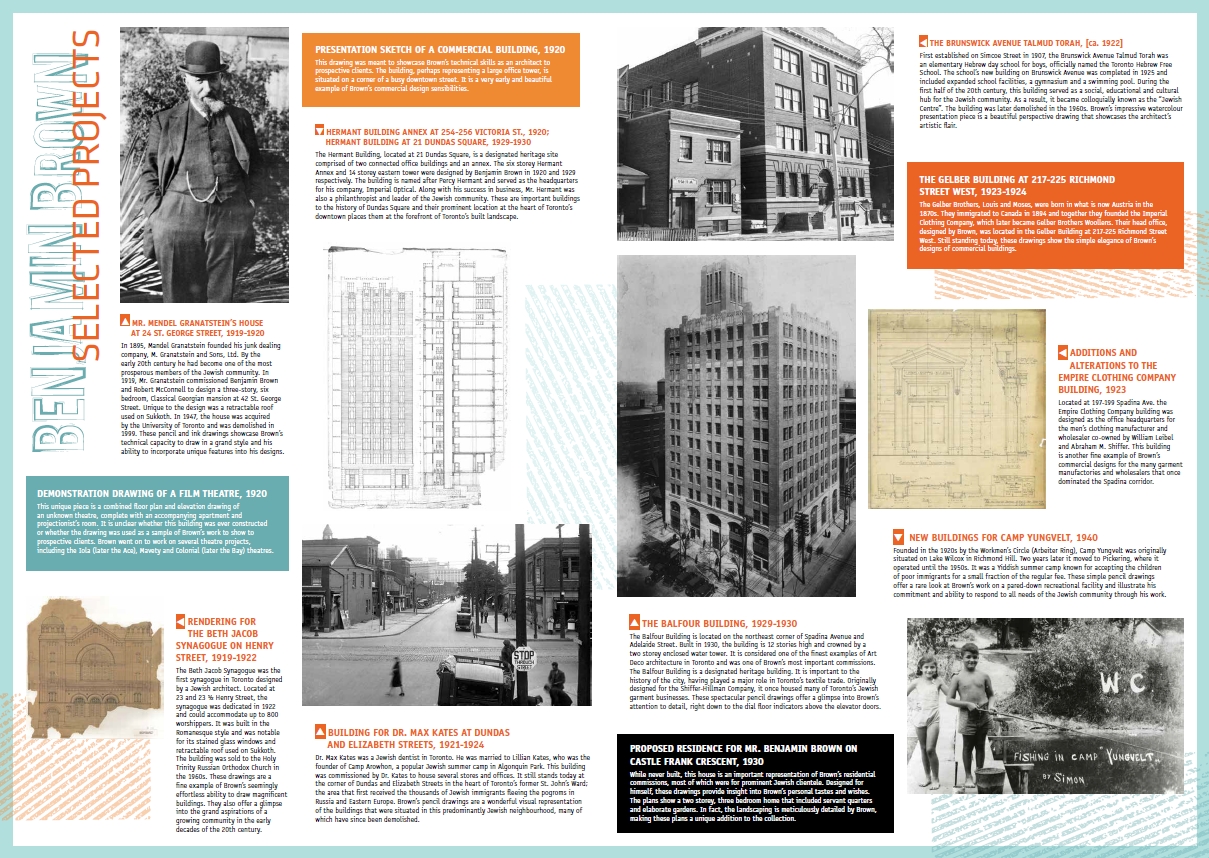

Selected Projects

Please click here to enlarge (pdf will open)

The Conservation Work has Begun!

Forty-one rolls and six boards consisting of hundreds of Brown’s drawings have been delivered to the conservator. Here’s a look at what has occurred during this first stage of conservation work.

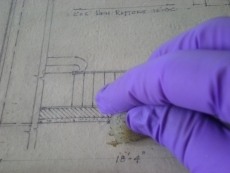

Many of Brown’s drawings have been tightly rolled for decades – some since the 1920s! Tight rolls are a problem for access as unfurling them puts undue stress on the documents and poses a risk for tears and cracks. It is also makes it difficult to assess other condition issues that may be present.

Therefore, one of the first steps in the conservation process is humidification. Humidification is a treatment used to slowly and gently unfurl documents by indirectly re-introducing moisture into the paper. There are many different ways of accomplishing this; the most common is by creating a humidification chamber.

Inside the chamber is a bottom layer of moisture absorbing material (such as goretex), which allows for the slow release of moisture without the risk of submerging the documents in water. A buffer layer usually made of grating and interleaving tissue further separates the documents from the wet layer below. The whole chamber is then covered to contain the humidity.

Over several days, as the drawings absorb more moisture they gradually become more pliable. They can then be placed under weights to prevent re-rolling. If space permits, storing plans flat is the optimal way to ensure their longevity and provide easy access to researchers.

Once the drawings have been unfurled, they can be better assessed for other conservation issues. Surface cleaning, spot cleaning and tear repair are common paper conservation procedures. Often, missing pieces containing valuable information need to be reattached or foreign substances removed.

Other types of treatments will need to be performed, depending on the drawing and the severity of damage. Acidic backings will be removed or support backings attached, and the entire collection will be rehoused in specially-designed boxes and folders.

Stay tuned for more updates!

Exhibition

Urban Space Gallery

401 Richmond Street West, Toronto

February 10-April 23, 2016

Find Out More About the Exhibit

Through the presentation of original architectural drawings, historical photographs, maps and a video documentary, this multi-media exhibition will position Benjamin Brown as one of Toronto’s most important early leading architects. Intricately rendered architectural details as well as beautifully painted façade drawings and presentation pieces will document the breadth and range of Brown’s accomplishments in the commercial, industrial, corporate, religious, and residential landscape. These buildings will be explored within the context of Brown’s career, Toronto’s architectural heritage, and the growth of the Jewish community during this time.

The exhibition will also illuminate the conservation process by showing the various methods used to conserve and preserve this extraordinary collection. A short documentary film will also be on view that explores contemporary perspectives on Brown’s buildings that stand as testaments to the past while re-purposed for today.

Jay Levine on How the Records Arrived at the OJA

In late 1972, my late mother, Rochelle Levine, was researching the Henry Street Shul for a course at the University of Toronto. Looking to locate the original drawings, she discovered that the architect – Benjamin Brown – was one of the first Jewish architects in the city. My father Jim, as a practicing architect himself, knew that the building department would loan out the permit drawings as long as the original architect gave permission.

In late 1972, my late mother, Rochelle Levine, was researching the Henry Street Shul for a course at the University of Toronto. Looking to locate the original drawings, she discovered that the architect – Benjamin Brown – was one of the first Jewish architects in the city. My father Jim, as a practicing architect himself, knew that the building department would loan out the permit drawings as long as the original architect gave permission.

Initially told that the architect had died, he persisted, finding out that Ben Brown was alive and well and living in the Annex just off of Avenue Road south of Davenport. Mr. Brown, then 82, was so surprised that anyone would still be interested in his work, he not only gave his permission to borrow the drawings, but initiated a friendship with my parents that lasted until his death in December of 1974. During that time Jim made arrangements to have him reinstated in the Ontario Association of Architects, and Mr. Brown was so grateful that he bequeathed his entire life’s architectural work to him.

After Brown’s death, Jim went to retrieve the drawings from his home to find a dusty and deteriorating collection piled around, on top of and even inside of an old Edsel. It took a total of six trips to get it all, and for the next 13 years they sat in the mezzanine storage of Jim’s office on Consumers Road. Unsure of what to do with the “Ben Brown Pile”, we contacted the Centre for Canadian Architecture in Montreal, who was uninterested in the collection, considering it the work of a minor regional talent. They suggested calling Dr. Stephen Speisman, then Director of the Ontario Jewish Archives who could advise whether there was anything worth saving. When Dr. Speisman saw what we had, he could hardly contain his excitement.

![Balfour Building, northeast corner of Spadina and Adelaide, Toronto, [ca. 1930]. Ontario Jewish Archives, item 3308. Balfour Building, northeast corner of Spadina and Adelaide, Toronto, [ca. 1930]. Ontario Jewish Archives, item 3308.](https://ontariojewisharchives.org/cms_uploads/images/albums/Benjamin-Brown/F49-s3-f105_i3.jpg) Undoubtedly, you have probably stood in one of Benjamin Brown’s buildings, or if not, have certainly seen the many examples of his work around the city. His designs are beautiful and the documents that guided their construction are equally as beautiful. I am so grateful to Jim and Rochelle Levine for seeing the value of the records and for getting it into the hands of the OJA, where it can be preserved for posterity and made available to the community. The OJA has done a lot of work documenting the collection and protecting it from further decay. It is now time to conserve this important body of work for future generations, and we hope that you will consider contributing to the cost of conserving this very important chapter in our collective history.

Undoubtedly, you have probably stood in one of Benjamin Brown’s buildings, or if not, have certainly seen the many examples of his work around the city. His designs are beautiful and the documents that guided their construction are equally as beautiful. I am so grateful to Jim and Rochelle Levine for seeing the value of the records and for getting it into the hands of the OJA, where it can be preserved for posterity and made available to the community. The OJA has done a lot of work documenting the collection and protecting it from further decay. It is now time to conserve this important body of work for future generations, and we hope that you will consider contributing to the cost of conserving this very important chapter in our collective history.

Jay Levine

nxl Architects