COLLECTING OUR COMMUNITY’S HISTORY ONE FAMILY AT A TIME: THE GRYFE BAKING DYNASTY

By Dr. Cyril Gryfe

Shlome Graif learned the bread-baking craft in Romania from his father as did Shlome’s older brother, Zacharia. In 1910, Shlome followed his two older sisters to Hamilton, Ontario, where, at first, he was unable to find work as a baker. His experience in a hot and dusty work environment proved to be an asset in tolerating his thankfully brief role as a labourer in the foundry of Hamilton’s International Harvester Company. Eventually he was employed by a local Jewish bakery. Around 1916, he became the independent baker, Sam Gryfe, York Street, Hamilton.

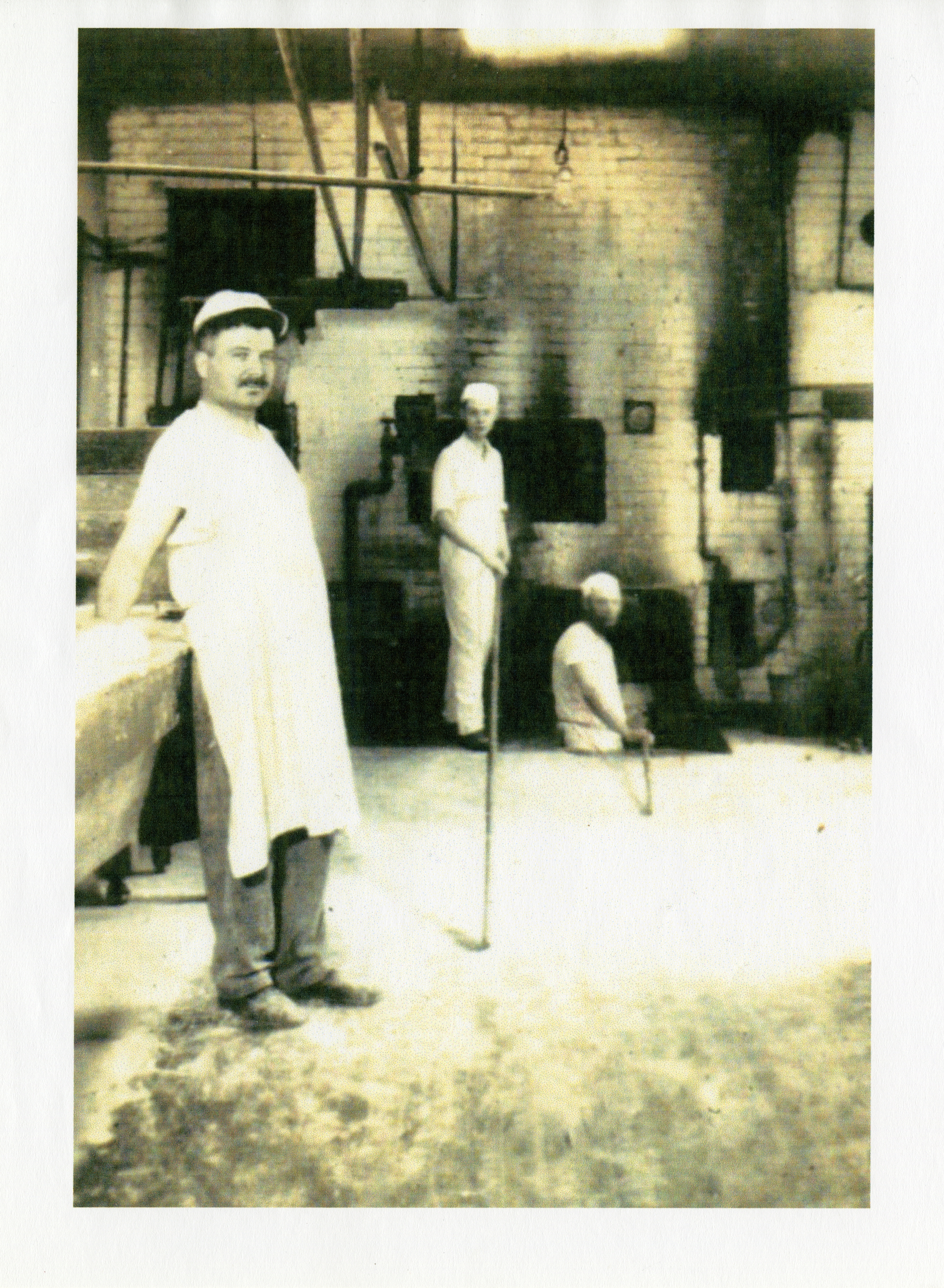

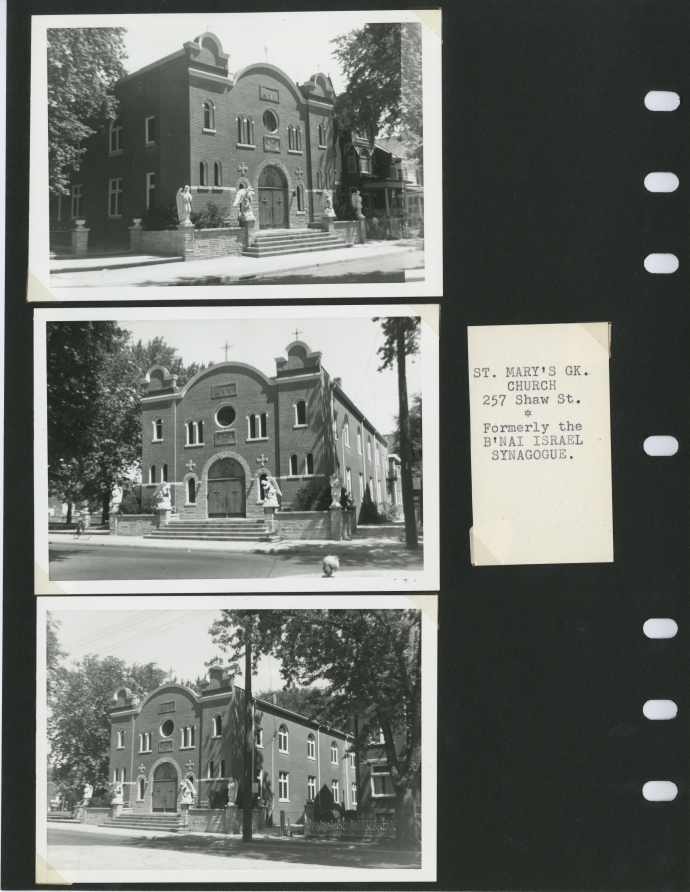

By 1920, relations between the two brothers and the two sisters appear to have cooled, and Sam and Zach (now Jack) moved to Toronto. After working in Aaron Perlmutar’s bakery at 175 Baldwin Street for a few years, Sam again decided to exercise his independence and in 1925 acquired the property at 319 Augusta Avenue, for which an oven needed to be built.

Nearby, on Major Street he found bricklayer Lipa Green, who, although certainly experienced in building fireplaces and chimneys, confessed that he had never before built a baker’s oven. Sam, however, had built at least one outdoor oven in Hamilton, and Mr. Green thus learned a new skill, which was subsequently the basis for his three sons to also learn the craft of bricklaying.

While Sam and Molly were raising their children, their expectation was that the offspring would join the family business. Firstborn Bill resisted the task of actually baking, but became the very effective sales agent for the business. He started as a pre-teen with sister Ida, as the two peddled kaiser rolls on city streetcars from a large, wheeled wicker basket.

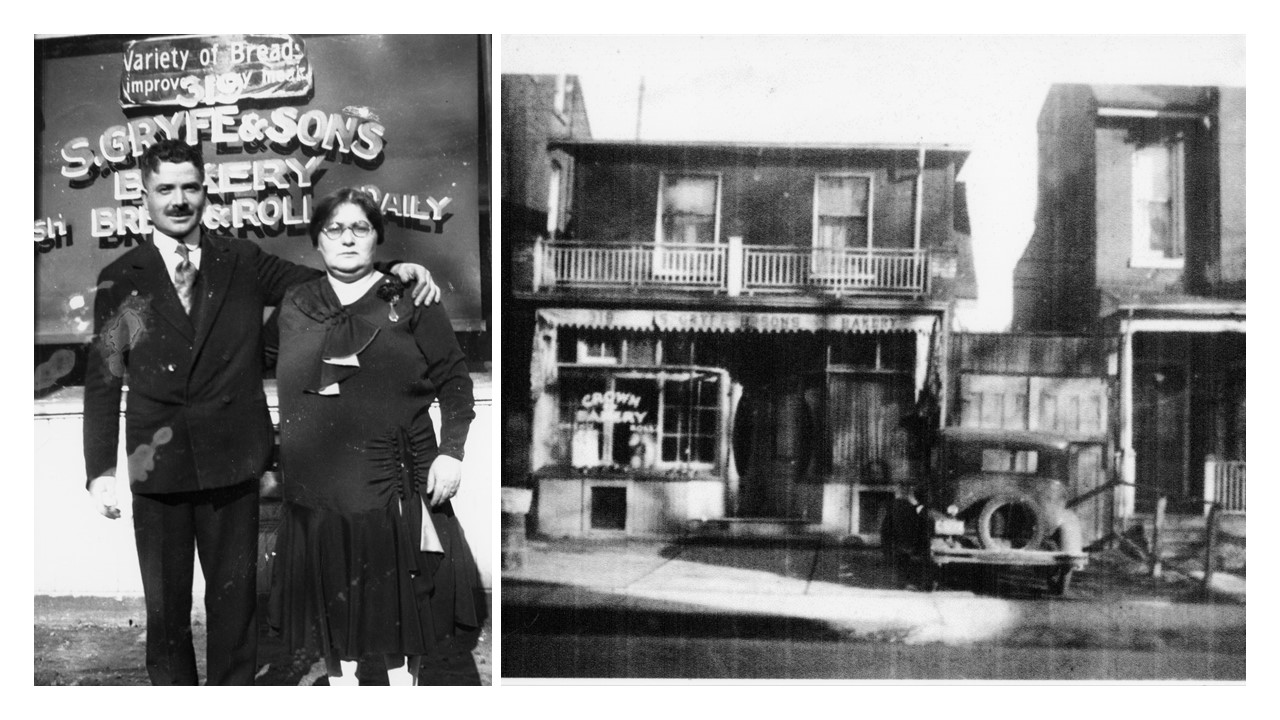

Second son, Art, apparently harbored ideas of becoming an engineer or an architect, but Sam was insistent, and Art, followed by Ben, then Srul all became skilled bakers—their participation in the family business first proudly proclaimed in 1930 as “S. Gryfe & Sons Bakery.”

Bill’s outside interests included athletics, which led him to create a club with its gym in part of the bakery building. and the club was named the Crown Athletic Club after a suggestion from one of the club members. By 1936, the sign on the window at 319 Augusta Avenue had become “Crown Bakery.”

Like his father, Art had aspirations of independence. In 1938—after marrying Ruth Price—he went to work in Philip Newman’s National Bakery at 404 Spadina Avenue for about five years. In 1945, he was a partner of Louis Silverberg in Atlas Bakery on St. Clair Avenue West. Shortly thereafter, he ventured out with Ruth to acquire Chisholm’s Bakery at 298 Queen Street East. Persevering through five setbacks over the following ten years (including relentless antisemitism at the Queen Street location) Art and Ruth finally grasped success when, in 1957, they acquired Esther Sky’s Bakery at 3435 Bathurst Street, which has become famous as Gryfe’s Bagels.

The story of the recipe for the bagels that finally rewarded Art and Ruth has several very different versions, but whatever may be the actual history of the bagels’ recipe has been made irrelevant by the bagels’ unique quality that perpetuates their fame.

Remaining bakers Ben and Srul drifted away from the family business, and in 1947 Sam sold Crown Bakery to Ben Richman and Max Hartstone, who in 1952 changed the name to Crown Bread and expanded to include 311 Augusta Avenue. However, Sam could not abandon his lifelong and familial devotion to baking and in 1950 opened a bakery in Jackson’s Point, Ontario, where he and Molly worked until their retirement and return to Toronto in 1955. In 1954, Crown Bread opened a branch at 1246 Eglinton Avenue West, but both sites were closed by 1963.

Sam’s brother, Jack, also adhered to the family’s baking legacy. After they moved to Toronto, Jack worked at Samuel Zimmerman’s bakery at 17 Phoebe Street, before venturing out himself in the mid 1920s on Kensington Avenue. By the mid 1930s he was firmly established at 4 Fitzroy Terrace, where he lived and worked until retiring in 1952.

Jack’s eldest child, Morris, also learned the craft from his father. After working for Canada Bread for a few years, he and his wife Jean moved to Phoenix, Arizona, where she enjoyed a more favorable climate for her chronic respiratory illness, and Morris (now known as Murray) continued to work as a baker.

Cyril Gryfe is a retired physician, who specialized in geriatric medicine. Listening to his patients report their medical symptoms within the context of their long and often complicated life stories, perpetuated and reinforced his interest in history in general, which had been kindled during high school studies. Throughout his professional career this was focused on the history of medical practice, and in more recent years he has also devoted much time to the genealogy of his extended family.

Cyril Gryfe is a retired physician, who specialized in geriatric medicine. Listening to his patients report their medical symptoms within the context of their long and often complicated life stories, perpetuated and reinforced his interest in history in general, which had been kindled during high school studies. Throughout his professional career this was focused on the history of medical practice, and in more recent years he has also devoted much time to the genealogy of his extended family.

By the next day I had moved onto the J. B. Salsberg fonds, which provided both a fascinating and intimate look at the history of Communist politics in Toronto, alongside a healthy amount of mid-century graphics. On my supervisor Faye’s suggestion, I even completed a weeks’ worth of posts about the history of Jewish cinema in Ontario, the archives hosting a decent collection of photographs of the glitzy art deco architecture of twentieth-century theatres.

By the next day I had moved onto the J. B. Salsberg fonds, which provided both a fascinating and intimate look at the history of Communist politics in Toronto, alongside a healthy amount of mid-century graphics. On my supervisor Faye’s suggestion, I even completed a weeks’ worth of posts about the history of Jewish cinema in Ontario, the archives hosting a decent collection of photographs of the glitzy art deco architecture of twentieth-century theatres.

Bronwyn Cragg is a fourth year undergraduate student of Jewish studies, German, and art history at the University of Toronto. His present research interests include fascism and the Holocaust in WWII Romania, and he has recently written works on art, aesthetics, and nation building in Mandatory Palestine. Bronwyn is currently studying Yiddish and seeks to continue his studies through translation, original research, and archival work.

Bronwyn Cragg is a fourth year undergraduate student of Jewish studies, German, and art history at the University of Toronto. His present research interests include fascism and the Holocaust in WWII Romania, and he has recently written works on art, aesthetics, and nation building in Mandatory Palestine. Bronwyn is currently studying Yiddish and seeks to continue his studies through translation, original research, and archival work. Starting this week, instead of biking past the Miles Nadal JCC on my way to the University of Toronto’s St George campus, I’ll be taking the Bathurst bus north to the Ontario Jewish Archives. I recently graduated from the University of Toronto’s Master of Information program, where I specialized in archives and records management. I spent the past two years working at the University of Toronto Libraries’ web archiving program, and the past year volunteering at The ArQuives (formerly the Canadian Lesbian & Gay Archives), where I am currently processing the Inside Out LGBT+ Film Festival fonds.

Starting this week, instead of biking past the Miles Nadal JCC on my way to the University of Toronto’s St George campus, I’ll be taking the Bathurst bus north to the Ontario Jewish Archives. I recently graduated from the University of Toronto’s Master of Information program, where I specialized in archives and records management. I spent the past two years working at the University of Toronto Libraries’ web archiving program, and the past year volunteering at The ArQuives (formerly the Canadian Lesbian & Gay Archives), where I am currently processing the Inside Out LGBT+ Film Festival fonds.