Looking Back on The Penny Rubinoff Fellowship

By Renée Saucier

I was initially attracted to the Penny Rubinoff Fellowship because of the opportunity to engage in all aspects of the archival field in a community archives setting (see my previous post), and I am pleased to report that that is exactly what I’ve been doing. I’ve been working in several areas and on several projects, all with the shared aim of providing access to documentation of the Jewish experience in Ontario.

In addition to developing my skills as an archivist, I’ve been gaining a deeper understanding of the matrices of relationships underpinning this particular community archives. Community archivists work with records, but the core of their work consists of building and maintaining relationships with records donors (and their families), educators, partner organizations, researchers/users, volunteers, board members, financial supporters, and other community members. ‘Community’ itself is a messy/complex term, for any given community has contested boundaries and is in fact composed of multiple overlapping communities—in the OJA’s case, communities that are spread throughout and across the province. Each day, I learn more about the religious, ethnic, racial, political and linguistic diversity of Ontario’s Jewish communities, and my time here has been an opportunity to learn how the OJA’s dedicated staff approach their work and undertake to preserve and share back documentation of the diverse range of experiences of Ontario’s Jewish communities.

Collections Development & Donors

I have had the opportunity to work one-on-one with donors to advise on and coordinate the donation of records to the Ontario Jewish Archives. As well, I have been working to help build the OJA’s collections through the Bathurst Manor Project, the OJA’s major collections development initiative for 2020. (You’ll hear more on that in the coming months!) I have surveyed our current holdings, identified and consulted relevant holdings elsewhere, and helped to plan focus group meetings to determine our collecting priorities.

Welcoming New Materials into the Archives

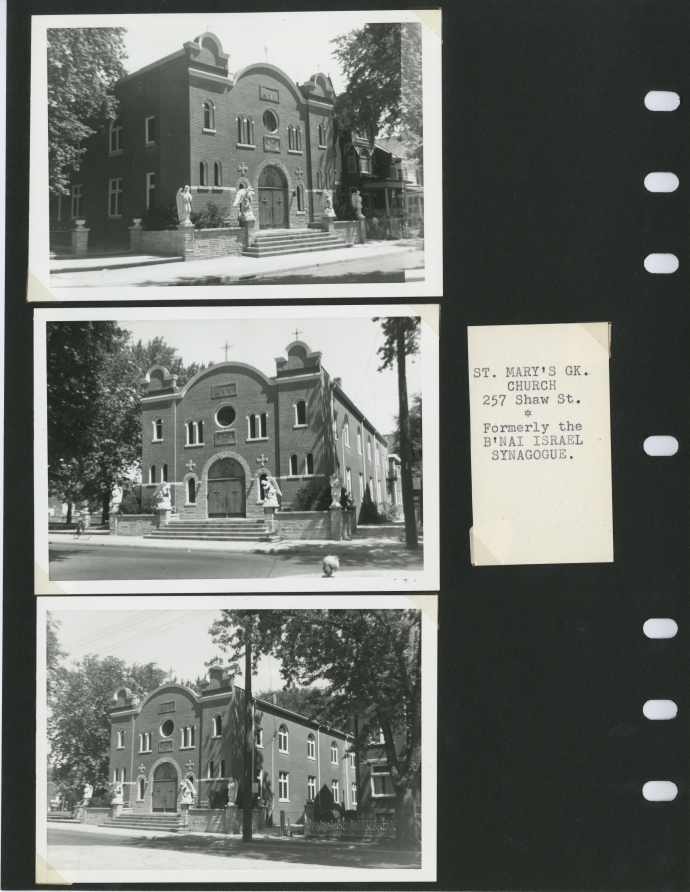

I spent my first few weeks accessioning new collections. This was a means for me to familiarize myself with the OJA’s holdings and procedures, as well as a way to help reduce the current backlog (…every archive has one!) I’ve accessioned a variety of media including textual records, photographs, slides, and film. Along the way I’ve learned about the OJA’s procedures for rehousing different media and have also had the opportunity to develop appraisal criteria. One highlight was an accession of photographs and slides created by Stephen Speisman and donated by Bill Gladstone; these images capture downtown Toronto synagogues in the 1960s-70s, documenting the changing use of the buildings as congregations merged and/or moved northward.

Making Records Accessible

One of my main projects has been processing records created and accumulated by the Executive Director/CEO of the UJA Federation of Greater Toronto. These records occupy a dozen banker’s boxes and span the late 1970s through the 2000s. Given the high-level nature of the work done by this office, the records pertain to a variety of activities involving an array of partners and groups, documenting initiatives ranging from integration services for Soviet Jewish immigrants in the 1980s to the formation of an AIDS Task Force and Policy in the early 1990s.

I have a personal interest in the history of information and communication technologies, and these records offer portals into the materiality of that history. For example, there is an observable shift in the medium of correspondence from typewritten documents and signed letters to faxes and then printed-off emails. Meeting minutes and budget proposals document the adoption of new technologies, including the establishment of an “online Internet presence” and a “Jewish Information Highway”. On a related note, I am excited to be on board to observe and learn about the OJA’s process in selecting and introducing a digital preservation program to preserve born-digital materials documenting Ontario’s Jewish communities.

Access: Behind the Scenes, Behind the Screens

I have also been supporting my colleague Faye with the OJA’s social media outreach, brainstorming, researching and designing posts for Facebook and Instagram. One focus here has been to feature ‘behind the scenes’ posts every week to enhance our audience’s understanding of archives and the work that takes place in them. We’re going to be featuring highlights from the Koffler family fonds, sharing both the materials and also the processes by which they are cared for and made accessible. One of the goals of our social media strategy is to convey the historical significance and importance of family and individual records and to encourage others to donate their materials to the archives.

One of my most enjoyable responsibilities has been providing reference services to researchers over email and in person on topics ranging from war criminals to revolutionary youth to family-run businesses in Kensington Market. Some researchers come to the OJA in order to recover details of stories that they were never fully told, such as a parent or grandparent’s immigration to Canada. Their experiences here demonstrate how community archives can support an individual in attaining a deeper understanding of themselves, their family’s history, and their relationship to larger historical events. Other times, researchers who aren’t expressly researching Jewish history in Ontario contact the archives because their topics (such as radical leftist organizing) have an historic association with segments of the Jewish community and are therefore richly documented in our holdings. These cases demonstrate the important role of community archives in supporting collective memory not only for their direct community, but for all of society.

By the next day I had moved onto the J. B. Salsberg fonds, which provided both a fascinating and intimate look at the history of Communist politics in Toronto, alongside a healthy amount of mid-century graphics. On my supervisor Faye’s suggestion, I even completed a weeks’ worth of posts about the history of Jewish cinema in Ontario, the archives hosting a decent collection of photographs of the glitzy art deco architecture of twentieth-century theatres.

By the next day I had moved onto the J. B. Salsberg fonds, which provided both a fascinating and intimate look at the history of Communist politics in Toronto, alongside a healthy amount of mid-century graphics. On my supervisor Faye’s suggestion, I even completed a weeks’ worth of posts about the history of Jewish cinema in Ontario, the archives hosting a decent collection of photographs of the glitzy art deco architecture of twentieth-century theatres.

Bronwyn Cragg is a fourth year undergraduate student of Jewish studies, German, and art history at the University of Toronto. His present research interests include fascism and the Holocaust in WWII Romania, and he has recently written works on art, aesthetics, and nation building in Mandatory Palestine. Bronwyn is currently studying Yiddish and seeks to continue his studies through translation, original research, and archival work.

Bronwyn Cragg is a fourth year undergraduate student of Jewish studies, German, and art history at the University of Toronto. His present research interests include fascism and the Holocaust in WWII Romania, and he has recently written works on art, aesthetics, and nation building in Mandatory Palestine. Bronwyn is currently studying Yiddish and seeks to continue his studies through translation, original research, and archival work.