Researcher Spotlight: Gesa Trojan

Stirring the Pot in Toronto and Berlin: Researching Toronto’s Jewish Food History from Both Sides of the Atlantic

I came to Toronto as an outsider. In April 2016, alien to the city and its Jewish community, I found myself standing at a bus stop on Bathurst Street, freezing in my light jacket, facing not only the Torontonian weather, but also the challenge of collecting source material for my dissertation on Toronto’s Jewish food history. For my thesis, I am employing food as a research perspective to study the linkages between Jewishness and class in everyday life in early 20th-century Toronto. Back in Berlin, I had prepared for my temporary stay in Toronto, but now that I had made it to the other side of the Atlantic, I felt nervous: How would I find my way through the city and, far more challenging, its Jewish history? When I arrived at the Ontario Jewish Archives I knew, though, that my nervousness was unwarranted. I have never found a warmer or more welcoming place to work.

My doctoral thesis is my first big archival project. During the months at the researcher’s table in the OJA, quietly sorting through the material that Donna, Melissa, Faye, and Michael pulled for me from the vaults, I learned how an archive works. For historians, it is important to understand how archival material is organized, stored, and made available. This was particularly true for me, working on a fuzzy topic like food. The relevant sources would not simply show up by typing in “food” in the search box. Unlike libraries, where I used to work, archives are not organized by subject. There was no box at the OJA labelled “food.” Not surprisingly, I regularly felt overwhelmed by my task. But I was lucky, because the whole staff patiently helped me locate relevant material for my inquiry.

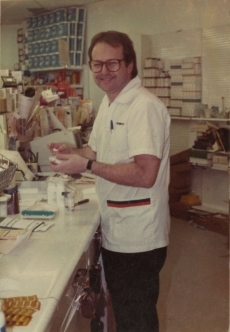

The OJA records, which would help me pursue my research on Jewishness and food, were scattered islands organized into multiple fonds and accessions. Digging them up was a labor-intensive task. I didn’t mind spending my days like this, though, because the sources were so rich and palatable that I often became oblivious to everything around me while reviewing them. I hungrily devoured the Naomi Cook Books published by the upper-class Hadassah women of Toronto from 1928 until 1964. The struggles of the Jewish labor movement, which I encountered, brought forth another unexpected insight into Jewish foodways: heated debates about workers’ rights would erupt over hot split pea soup at United Bakers Dairy Restaurant, where the Jewish left often congregated. Box by box and document by document, the days of my research trip flew by, and soon I would return to Berlin. At this point, I felt the cornucopia of sources that the OJA held turning against me: How was I supposed to soak up all the information that was still there waiting for me?

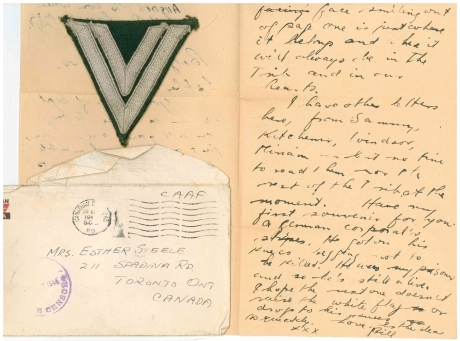

Luckily, I discovered two insights that are life-saving for a PhD student. First of all, I don’t have to absorb everything. Secondly, the OJA’s staff have set up an excellent infrastructure that allows for archival research regardless of the oceans that may lie between the writer and her sources. Many records are digitized. From Berlin, I can order digital copies of oral histories, photographs, and films. Through its website, the OJA offers access to the Toronto Jewish City Directories, published in the 1920s and 1930s, which proved to be essential sources for my project. The OJA also has a team of researchers on site, allowing me to hire someone from afar to help me tackle the more demanding tasks. Notwithstanding this excellent setup, I hope to be back at the OJA soon, as I especially enjoyed the tactile dimension of working with historical records. Touching the fragile pages of a letter sent seventy years ago, noticing a detail that might have been ignored until now, made me feel completely contented.

Approaching the past with questions that have not been asked before is simultaneously the starting point and the impediment of all historiography. The historians’ endeavor is difficult, because their research interests change over time, while the source material mainly stays the same. We keep stirring the same pot with different spoons. Historical scholarship is based on the historical archive. Archivists preserve records in a storage memory that allow historians to interpret and reinterpret the multitude of stories that the letters, photos, and documents might tell. During the last weeks of my residency, Michael, one of the archivists, took me on a tour through the OJA’s vaults. For a short time, I stood at a spot where the dates on the materials around me transcended an individual lifespan; where past, present and future related. The acid-free boxes and folders that the OJA staff lovingly stores for generations of researchers to come are filled with endless stories waiting to be told. I feel humbled and deeply grateful for the warmth and support I encountered at the OJA during my endeavor to unravel one of those stories.

Gesa Trojan

PhD candidate, Center for Metropolitan Studies at Technische Universität Berlin

![Jewish Labor Committee, [194-?]. Ontario Jewish Archives, Blankenstein Family Heritage Centre, fonds 10, item 29.](https://ontariojewisharchives.org/cms_uploads/images/F10_i29.jpg)

![Eli Bloch in South Africa during the Boer War, [1900?]. OJA, accession #2016-7/9.](https://ontariojewisharchives.org/cms_uploads/images/quotes/2016-7-8_005.jpg)