Rabbis

In the early years, starting perhaps with Mr. Nobelman in the 1920s, a series of individuals were engaged by the Niagara Falls community to serve their religious needs. Their responsibilities typically included the ritual killing of chickens in the kosher manner, offering instruction to the children and leading the congregation in prayers, especially during the High Holy Days. Though these men may have received rabbinic ordination from their own rabbis in Eastern Europe, they were not professionally trained rabbis, like the ones who graduated from America’s seminaries.

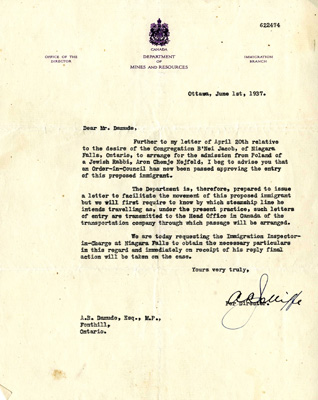

A succession of other men followed Nobleman, some staying for longer and others for shorter periods. As one community member commented, “some of them were wonderful and others just awful.” One rabbi was suspected by the community of being a Torah thief: he would send Torahs out for repair and they did not come back. Another was a drinker. The fact is that good rabbis were often reluctant to serve in small communities. In 1937, for instance, the congregation recruited a rabbi from Poland, Aron Nejfeld, who was twenty-five years old and single. Due to the restrictive nature of immigration at this time, they were required to request an Order-in-Council – PC 685 -- be passed in order to approve his entry into Canada. Once it was approved, the Department agreed to support their request and Rabbi Nejfeld was permitted to immigrate to Canada. They seemed to sympathize with the congregation after hearing that there were only 32 families in town, and that nine of them were said to be carrying the financial burden of the synagogue.

Throughout the years, it was very difficult for the synagogue to secure and hold onto rabbis. If the man was married, the absence of a large community offering day school education for his children could be a serious deterrent. Dr. Joseph Klinghoffer, Educational Director for the Canadian Jewish Congress, expressed this succinctly in a letter to then synagogue president Irving Feldman, in March of 1966: “There is no need to restate how difficult it is to find the right man for a smaller community.”

Rabbi Green was a Holocaust survivor who served the community during the late 1940s until the early 1950s. He is remembered with gratitude by Irving Milchberg, a survivor who had had difficulty involving himself in Jewish life after the war. Thanks in part to Rabbi Green’s empathy, Milchberg was able to return to the fold, something he wanted to do especially for the sake of his children. Rabbi Green was followed by Rabbis Lieberman, Kutziner Fleischmann, Yehuda Fleischmann, Feier, Yitzhak Gross and Nathan Lieberman. In the early 1960s, when Rabbi Fleischmann was the congregation’s spiritual leader and teacher, he organized a “tefillin club” and discussion group, while his wife taught the children Hebrew. After leaving Niagara Falls, Fleischmann shifted careers and became a day school educator, working as a principal in Kansas City, Milwaukee and California and teaching in Atlanta and Maryland.