| INTRODUCTION

By

Dr. Stephen Speisman

A Jewish presence in Toronto was evident as early as the

1830s and by the mid-1850s, there were eighteen Jewish

families in the city. Primarily of English origin, some

having come via Quebec or the United States, these first

families established the first synagogue in Toronto in

1856. The congregation consisted of craftsmen, small shopkeepers

and merchant importers.

Following the 1880s, religious persecution and economic

hardship attributable to the Industrial Revolution forced

large numbers of Jews to leave Eastern Europe --- Lithuania,

Russia, Poland, Austria-Hungary, Romanian.1

Those who settled in Toronto, as elsewhere in North America,

quickly outnumbered the original Jewish inhabitants and

established their own religious, cultural, educational

and social institutions.

By 1900, synagogues had begun to proliferate, at first

divided by country of origin and later, as the population

increased, by regions and towns in Eastern Europe. These

congregations --- orthodox without exception -- set up

in private dwellings or storefronts (shtiblach) and later

in vacated churches and purpose-built structures.

In the decades prior to the First World War, Jewish afternoon

schools, both secular and religious were founded, as well

as Yiddish![Yiddish: [literally, "Jewish"] language spoken by Jews in Eastern Europe. Yiddish is a blend of Hebrew and German, but is written using Hebrew characters.](images/g.gif) theatres, a newspaper, and mutual-benefit societies.

theatres, a newspaper, and mutual-benefit societies.

These East European Jews began as peddlers, artisans or

factory workers in the clothing industry, although some

later opened small retail shops and factories, ultimately

achieving greater status as wholesalers, waste processors

or real estate investors. Their children would eventually

enter the professions.

Although the English Jews settled east of Yonge Street,

in still-fashionable streets which had not yet begun to

deteriorate, the East European immigrants found both housing

and employment in St. John’s Ward, a slum between

Teraulay Street (now Bay) and University Avenue, which

came to be known simply as “The Ward”. Here,

the Jews attempted to create many of the features of their

old homes in Europe. The Ward became, in many ways, a

North American shtetl ---- a Jewish village --- where people gathered in restaurants,

groceries and confectionery shops. It all fostered a sense

of security in a hostile environment where these poverty-stricken

immigrants evoked fear in the minds of the native Anglo-Saxon

citizens, who passed through the Ward by streetcar on

the way to the fashionable downtown stores.

---- a Jewish village --- where people gathered in restaurants,

groceries and confectionery shops. It all fostered a sense

of security in a hostile environment where these poverty-stricken

immigrants evoked fear in the minds of the native Anglo-Saxon

citizens, who passed through the Ward by streetcar on

the way to the fashionable downtown stores.

For traditional Jews, the synagogue was also a place of

refuge. It was a social centre where one could interact

with those who shared the same experience, who knew your

family in the alter heim .

The synagogue often offered free loans, assistance to

the sick and destitute, a cemetery and place where one

could achieve the social status unavailable outside its

walls. A peddler could become a president, a gabbai .

The synagogue often offered free loans, assistance to

the sick and destitute, a cemetery and place where one

could achieve the social status unavailable outside its

walls. A peddler could become a president, a gabbai (warden) or the holder of some other respected office.

And of course, it was a place to study the divine word

and to pray to their Creator, with whom many felt an intimate

relationship.

(warden) or the holder of some other respected office.

And of course, it was a place to study the divine word

and to pray to their Creator, with whom many felt an intimate

relationship.

The house or storefront synagogue often consisted of a

large room where the men prayed (with long tables and

chairs rather than benches), a women’s section,

perhaps on the main floor surrounded by a partition or

curtain, or an upstairs room with a grate in the floor,

through which one could follow the service downstairs.

A small kitchen was usually located adjacent to the main

room for the preparation of refreshments following the

services. A weekday chapel would have to wait until larger

premises were available.

Few of these congregations could afford a rabbi or cantor

in these early years. Most of the functions were carried

out by volunteers but assisted if possible by a paid sexton

who might also serve as reader, teacher and janitor.

As the Jews grew more prosperous, they sought to escape

the Ward, moving to areas where there were backyards and

parks in which their children could play, houses large

enough to accommodate recently-arrived relatives from

Europe, and indoor plumbing.

Since accessibility to the Ward was originally a factor,

as employment and relatives often remained there, the

Jews moved westward, following the streetcar lines along

College and Dundas streets between McCaul and Bathurst.

Spadina Avenue became the core thoroughfare and by 1917,

a full-blown outdoor market had developed just west of

it, along Kensington Avenue, Baldwin St. and Augusta Avenue.

On Spadina, itself, the portion south of Dundas became

a centre for the garment industry, with many of the factories

now operated by Jews, and the area north of Dundas offering

stores and restaurants to serve the local residents. By

the late 1920s, most of the Jewish population had vacated

the Ward, establishing their businesses in the Spadina

Avenue/Kensington Market district, bringing their institutions

with them or establishing new ones.

There

were a number of exceptions to this pattern of movement.

One was the Jewish community at "The Junction",

where a group of families settled at the turn of the twentieth

century, to be close to the industries that clustered

along the railway lines or, as peddlers in the countryside,

to get a head start on those peddlers traveling from the

Ward.

In addition, there were pockets of Jews in Cabbagetown

and in the Beaches, primarily shopkeepers who lived in

those areas to be close to their businesses. The Beach

community was supplemented by prosperous Jews who lived

in the central part of the city, but who had summer cottages

along the streets radiating north from Lake Ontario.

The Spadina Avenue/Kensington Market area remained the

heartland of the Toronto Jewry until the mid-1950s, when

a movement northward began, primarily following Bathurst

Street into Downsview and Bathurst Manor, then to Finch

Avenue and Steeles, and into Thornhill. While large numbers in the community continue to move even farther north into York Region, primarily between Dufferin Street and Leslie, Jews never abandoned the downtown area. In recent decades, downtown congregations have been revived, several new Jewish schools have been established, the renewed Miles Nadal Jewish Community Centre has become a Jewish cultural centre and the downtown Jewish population has increased substantially.

1

The Industrial Revolution came late to Eastern Europe,

its effects not being felt in the Russian and Austro-Hungarian

empires until the last quarter of the nineteenth century.

Those Jews who were artisans and petty merchants simply

could not compete with factories and railways.

Home

Synagogues Glossary

Site Map Contact

Credits Links

|

View of Spadina Avenue, north from Queen Street (1910)

Young boy in front of a house (1919)

Dundas Street, west of Bay Street (c. 1925)

Photograph of Dundas Street looking north to Royce Avenue

(1925)

Photograph of Brunswick Avenue north of Harbord Street

(1899)

Queen Street at Woodbine Avenue, 1919.

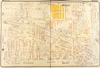

The Kensington area - Wards 4 and 5 (1923)

West Toronto Junction - Ward 7 (1912)

The Annex – Wards 4 and 5 (1923)

Map of the Beach area, 1924.

|